How Apache Flink™ handles backpressure

People often ask us how Flink deals with backpressure effects. The answer is simple: Flink does not use any sophisticated mechanism, because it does not need one. It gracefully responds to backpressure by virtue of being a pure data streaming engine. In this blog post, we introduce the problem of backpressure. We then dig deeper on how Flink’s runtime ships data buffers between tasks and show how streaming data shipping naturally doubles down as a backpressure mechanism. We finally show this in action with a small experiment.

What is backpressure

Streaming systems like Flink need to be able to gracefully deal with backpressure. Backpressure refers to the situation where a system is receiving data at a higher rate than it can process during a temporary load spike. Many everyday situations can cause backpressure. For example, garbage collection stalls can cause incoming data to build up or a data source may exhibit a spike on how fast it is sending data. Backpressure, if not dealt with correctly, can lead to exhaustion of resources, or even, in the worst case, data loss.

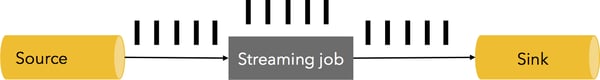

Let us look at a simple example. Assume a data streaming pipeline with a source, a streaming job, and a sink that is processing data at a speed of 5 million elements per second in its steady state as shown below (one black bar represents 1 million elements, the image is an 1 second “snapshot” of the system):

At some point, either the streaming job or the sink have an 1 second stall, causing 5 million more elements to build up. Alternatively, the source might have a spike, producing data at a double rate for the duration of one second.

How do we deal with situations like that? Of course, one could drop these elements. However, data loss is not acceptable for many streaming applications, which require exactly once processing of records. The additional data needs to be buffered somewhere. Buffering should also be durable, as, in the case of failure, this data needs to be replayed to prevent data loss. Ideally, this data should be buffered in a persistent channel (e.g., the source itself if the source guarantees durability - Apache Kafka is a prime example of such a channel). The ideal reaction is to “backpressure” the whole pipeline from sink to the source, and throttle the source in order to adjust the speed to that of the slowest part of the pipeline, arriving at a steady state:

Backpressure in Flink

The building blocks of Flink's runtime are operators and streams. Each operator is consuming intermediate streams, applying transformations to them, and producing new streams. The best analogy to describe the network mechanism is that Flink uses effectively distributed blocking queues with bounded capacity. As with Java's regular blocking queues that connect threads, a slower receiver will slow down the sender as soon as the buffering effect of the queue is exhausted (bounded capacity).

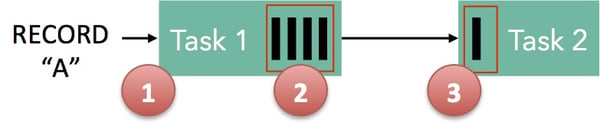

Take the following simple flow between two tasks as an example of how Flink realizes back pressure:

-

Record "A" enters Flink and is processed by Task 1.

-

The record is serialized into a buffer,

-

This buffer is shipped to Task 2, which then reads the record back from the buffer.

The central observation is the following: In order for records to progress through Flink, buffers need to be available. In Flink these distributed queues are the logical streams, the bounded capacity is realized via the managed buffer pools per produced and consumed stream. A buffer pool is a set of buffers, which are recycled after they are consumed. The general idea is simple: You take a buffer from the pool, fill it up with data, and after the data has been consumed, you put the buffer back into the pool, where you can reuse it again.

The size of these pools varies dynamically during runtime. The amount of memory buffers in the network stack (= capacity of the queues) defines the amount of buffering the system can do in the presence of different sender/receiver speeds. Flink guarantees that there are always enough buffers to make *some progress*, but the speed of this progress is determined by the user program and the amount of available memory. More memory means the system can simply buffer away certain transient backpressure (short periods, short GC). Less memory means more immediate responses to back pressure.

Take the simple example from above: Task 1 has a buffer pool associated with it on the output side and task 2 on its input side. If there is a buffer available to serialize “A”, we serialize it and dispatch the buffer.

We have to look at two cases here:

-

Local exchange: If both task 1 and task 2 run on the same worker node (TaskManager), the buffer can be directly handed over to the next task. It is recycled as soon as task 2 has consumed it. If task 2 is slower than 1, buffers will be recycled at a lower rate than task 1 is able to fill, resulting in a slow down of task 1.

-

Remote exchange: If task 1 and task 2 run on different worker nodes, the buffer can be recycled as soon as it is on the wire (TCP channel). On the receiving side, the data is copied from the wire to a buffer from the input buffer pool. If no buffer is available, reading from the TCP connection is interrupted. The output side never puts too much data on the wire by a simple watermark mechanism. If enough data is in-flight, we wait before we copy more data to the wire until it is below a threshold. This guarantees that there is never too much data in-flight. If new data is not consumed on the receiving side (because there is no buffer available), this slows down the sender.

This simple flow of buffers between fixed-sized pools enables Flink to have a robust backpressure mechanism, where tasks never produce data faster than can be consumed.

The mechanism that we described for data shipping between two tasks naturally generalizes to complex pipelines, guaranteeing that backpressure is propagated through the whole pipeline.

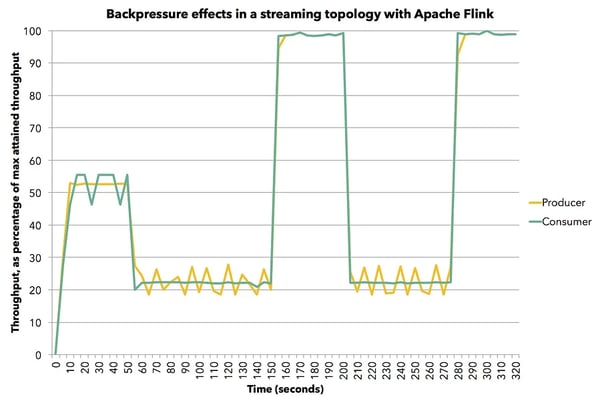

Let us look at a simple experiment that shows Flink’s behavior under backpressure at work. We run a simple producer-consumer streaming topology with tasks exchanging data locally, where we vary the speed at which the the tasks produce records. For this test, we use less memory than default to make the back pressure effects more visible for presentation reasons. We use 2 buffers of size 4096 bytes per task. In usual Flink deployments, tasks will have more buffers of larger size, which only improves the performance. The test is run in a single JVM, but uses the complete Flink code stack.

The figure shows the average throughput as a percentage of the maximum attained throughput (we achieved up to 8 million elements per second in the single JVM) of the producing (yellow) and consuming (green) tasks as it varies by time. To measure average throughput, we measure the number of records processed by the tasks every 5 seconds.

First, we run the producing task at 60% of its full speed (we simulate slow-downs via Thread.sleep() calls). The consumer processes data at the same speed without being slowed down artificially. We then slow down the consuming task to 30% its full speed. Here, the backpressure effect comes into play, as we see the producer also naturally slowing down to 30% of its full speed. We then stop the artificial slow down of the consumer, and both tasks reach their maximum throughput. We slow down the consumer again to 30% of its full speed, and the pipeline immediately reacts with the producer slowing down to 30% its full speed as well. Finally, we stop the slow-down again, and both tasks continue at 100% their full speed. All in all, we see that producer and consumer follow each other’s throughput in the pipeline, which is the desired behavior in a streaming pipeline.

Summary

Flink, together with a durable source like Kafka, gets you immediate backpressure handling for free without data loss. Flink does not need a special mechanism for handling backpressure, as data shipping in Flink doubles as a backpressure mechanism. Thus, Flink achieves the maximum throughput allowed by the slowest part of the pipeline.

You may also like

Meet the Flink Forward Program Committee: A Q&A with Lorenzo Affetti

Meet Lorenzo Affetti, a Program Committee member for Flink Forward 2025, ...

Outrun Fraudsters with Agentic AI and Ververica

Enhance fraud detection with agentic AI and Ververica's real-time stream ...

KartShoppe: Real-Time Feature Engineering With Ververica

Discover how KartShoppe leverages Ververica’s real-time feature engineeri...

Maximize Efficiency: How Ververica's BYOC Deployment Optimizes CAPEX and OPEX

Learn how Ververica's BYOC deployment leverages CAPEX and OPEX to optimiz...